from The Guardian, 8 January 2026, US time:

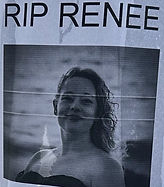

For Renee Nicole Good

killed by I.C.E. on January 7, 2026

by Amanda Gorman

They say she is no more,

That there her absence roars,

Blood-blown like a rose.

Iced wheels flinched & froze.

Now, bare riot of candles,

Dark fury of flowers,

Pure howling of hymns.

If for us she arose,

Somewhere, in the pitched deep of our grief,

Crouches our power,

The howl where we begin,

Straining upon the edge of the crooked crater

Of the worst of what we’ve been.

Change is only possible,

& all the greater,

When the labour

& bitter anger of our neighbors

Is moved by the love

& better angels of our nature.

What they call death & void,

We know is breath & voice;

In the end, gorgeously,

Endures our enormity.

You could believe departed to be the dawn

When the blank night has so long stood.

But our bright-fled angels will never be fully gone,

When they forever are so fiercely Good.

See also "Claims and Truths": https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/jan/09/white-house-minneapolis-ice-killing

The Last Time,

Sandra Rose Brand, 2025, Sydney

(based on a memoir by Long Vo-Phuoc,

oil on canvas, 100x100 cm)

Private Collection

Transcendental Red on Emerald Green

Is this what memories are made of? Is this what the electrons of the mind those eighteen years are now reduced to?

(Image courtesy: Leo Son, Youtube, "Nắng Chiều - Lê Trọng Nguyễn - AI Cover". Thanks.)

A Picture Says A Thousand Words

The photo adjacent was taken on 23 October 2025, showing US Congressman Dan Goldman (Democrats) “walks past federal immigration officers”. The latter were part of ICE, the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

These ICE “federal agents” were in court in the photo, facing away from camera, wearing mask to hide their face as customary these days, under Donald Trump, when doing such things as grabbing people from the streets, work places or home.

Web link for the photo: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/oct/30/ice-hidden-detention-sites from the international newspaper The Guardian.

Alice Munro, 1931-2024

It’s been a little more than a year now since Alice Munro passed away. In a recent conversation with a painter I happened to discuss a fine, finest, work of hers written in the 70s. My mind immediately cast over the times that I read her, in Sydney, Melbourne, Asia, Europe. Her books scattered on the sofa, the floor. Her books on the screens of the desktop, laptop. On the e-readers - Kobo, Kindle. On the bed of an hotel. On the dining table of a restaurant. On a bench next to a canal. On a bench inside a forest. On a plastic courtyard chair on an autumnal Sunday at a university.

Many commentators have breathlessly compared her to the famed Russian writer Anton Chekov. Some in France would compare her to Guy de Maupassant. Other names were mentioned: the English Somerset Maugham, the Irish William Trevor. Even the American John Updike. Perhaps the Chinese Lu Hsun. Some of the Vietnamese Vo Phien’s short stories may be placed alongside hers, too. Achievers at the highest level, all.

But still ... not quite so I would say, perhaps "far from it" in most instances. All these guys (guys, indeed!), were they still alive would only dream to write as she, to construct their works the way she did hers - with clear, seemingly simple yet incredibly lyrical but heart-stabbing prose. The way she brought (brings!) thoughts to your mind, makes you think of what you’ve just read, makes you think of the past you have known merged into the present and the future you might glimpse at in the years ahead. All these go through go past your mind your eyes when reading her. That is how it goes in every one of her hundred and twenty or so works of art.

She was, she is, alone reigning supreme in her art. A little lonely, perhaps, saddened by the scandal brought into light last year soon after her death. A scandal that was directly related to her action or, rather, lack of action. A soul-destroying sadness. I feel for her and her faults, for her daughter, yet Ms. Alice's works always stand out. Nothing can affect that, whatever she did or did not do in a part of life.

Long Vo-Phuoc, October 2025

Miss Marlene D, 1963, when her flowers had long lost to the wind, young boys young maidens all ...

Tỏ Tình Tuổi Già (Windy Bridge)

Hoàng-Tố Võ-Phước Long

(tháng Mười, 1975)

Một hôm tôi gặp em góc đường thành-phố. Em để tóc rối mặc áo đen đứng thật lẻ-loi.

Phải không Miện, một hôm tôi gặp em như thế. Hôm ấy thứ Bảy hay Chủ-Nhật. Đường ấy Elizabeth hay Castlereagh. Nhưng hề gì Miện yêu, thứ Bảy Chủ-Nhật là những ngày tha-huơng và Elizabeth Castlereagh muôn đời đại-lộ xứ nguời. Tôi gặp em và chuyến tàu dĩ-vãng ngùn ngụt kéo về nghiến nát tâm-hồn.

............. (more)

(see In Brief for description of the Pages)

(best viewed, and refreshed, in computer mode for correct layout)

The First Queen arrived this morning on the Magnolia, in front of the house. And Valentine, no less a Queen herself, quickly captured the fleeting loveliness.

Early Spring, 2025.

The Ogress’s Reply

(Saint-Germain, Mai 1955)

So, dearest Nga darling, you really want to know who I am?

You asked me that last night, remember? So this is the confession: I am an ogress, a mean and very hungry ogress, my diet consists solely of one substance, and that substance is you. I eat you up anytime, whatever your protest whatever your state of being. Eat you up, dearest darling, simply eat you up.

Any time we walk with each other on the streets, I wonder if strangers fathom the terrifying secret between us, between the two nice and not bad-looking (well, can’t deny that!) dames modernes, if they realise I can’t wait to get home and eat you up. I might appear pleasant, saying bon jour bon soir here and there to all and sundry, you may look cool and elegant and smiling (good to see you smile darling, Paris notwithstanding), but your fate is set at the end of each day, my meal would be ready, and you cannot run away, I won’t let you escape. Where are my long claws now, ah, they’re not protruding on the fingers just yet, but tonight they will be there for me to grab you, to bring your exquisite face closer to mine. Your fate is set as I said, set set set.

Nicole

Bà Chằn trả lời

(Saint-Germain, Mai 1955)

Vậy thì, Nga yêu thương của mình, vậy thì em muốn biết mình là ai?

Em hỏi mình như thế tối hôm qua, nhớ không? Thì đây là lời tự-thú: mình là bà chằn, một bà chằn vừa đói vừa hung-ác, một bà chằn chỉ muốn ăn miếng ngon độc-nhất, và miếng ngon ấy là Nga. Bà chằn muốn ăn Nga cho thoả phút giây nào cũng được, Nga mà cãi-cọ thế nào bà chằn cũng cứ ăn, cứ ăn ngay. Ngoạm ngoạm ngoạm thân-thể em, Nga yêu thuơng, bà chằn chỉ muốn ngoạm ngoạm em cho bỏ ghét!

Mỗi lần hai đứa mình dạo phố, mỗi lần như vậy mình không hiểu nguời ta có biết đến bí-mật khủng-khiếp giữa chúng mình, giữa hai cô nàng tân-thời tươi tốt đẹp-đẽ (không thể chối đuợc điều này), không hiểu họ có biết rằng mình, Nicole, chỉ muốn về nhà gấp gấp để ăn thịt Nga. Mình trông dáng bộ đàng hoàng, nói bon jour này nọ nguời này nguời kia, còn Nga thùy mị nhưng sao sắc-sảo và vô cùng sang-trọng với nửa nụ cuời (sung sướng bao nhiêu thấy nụ cuời của em, Nga, Paris hay không), nhưng số-phận em đã an-bài khi đêm đến, món cơm tối của mình sẽ dọn sẵn, món đó là Nga và em không thể nào trốn thoát. Đâu là móng nhọn của mình, à nó không trồi ra lúc này, nhưng đêm nay sẽ nhọn hoắc để mình vồ Nga trong hai bàn tay, để mình đem khuôn mặt diễm-ảo của em đến tận mật mình, vầ số- phận của em đã an-bài như đã bảo, đã an bài Nga vô-vàn thương yêu.

Nicole

An old war for the romantic souls

… and a long-ago short story

The half-civil half-foreign war in South Viet Nam during 1960-75 was a hard one for all involved. It was nasty. It suffered the remorseless aerial bombing carried out by the US on a small country, more than what the Americans dropped during the Second World War. It witnessed the murderous ruthlessness of the communist North (remember the 1968 Tet Offensive massacre in Hue?). It saw the unbelievable corruption and incompetence carried out by a government and its bureaucracy, that of the South, wasting so much of the hard cold money given by its sponsor the US. All the nastiness and hopelessness that a 15-year war could have mustered were there in full force. Two three million Viets were killed, most from the South, civilians, soldiers.

No wonder many thoughtful romantic souls when reading history long for a perhaps simpler, perhaps more just, more straightforward and, my deepest condolences for those Viets who had then fallen, perhaps a more romantic war. I know, we should never never speak of a concoction such as a romantic war. But what can I say, some of the finest and most affectionate poems in the world were written during this war (read, for example, some from Quang Dung, some from Nguyen Binh, Nguyen Huu Loan …, poet-soldiers all). It was the nine-year struggle against the French colonialists for Viet independence, 1946-54.

I deluded myself when I wrote “a simpler war”. No war is ever such. Even today’s fight against climate change is never accepted by a sizeable proportion of people around the world: simply go ask Donald Trump’s US administration and the large populace voting for him (that populace was not half of the US by the way, because voting is not compulsory there, 37% did not vote). Or go ask those who are religious and prejudiced against homosexuality. One would think, what kind of a nasty belief in god is that, why sex in the bedroom is any business of those so-called ambassadors of god? Want another example of life’s conundrums? Well, at its peak the 3-trillion-USD-Nivida drew in even more wide-eyed investment “analysts” and suckers’ money, then out came “BOOM”: Donald Trump jumped on the publicity stage with his dumb tariff war, hurting all and sundry, not least Americans, and Nvidia’s share price nose-dived.

In that noble war against French occupiers many Viet fighters (those against the French that is, because there were Viets paid by the mother country to fight for the masters) didn’t like the idea of fighting under Ho Chi Minh’s flag. Why? Many reasons: ideology (because communism was hard to swallow), governance (because the centralised way the communists ran their economy, their organisation, their bureaucracy, is even harder to stomach) and the nasty nuances in the communist conduct of a war machine. The worst example was this: say you joined the Viet Minh, you fought the French bravely under immense enemy fire during the day, exhausted when night came but still you had to watch your steps with the unit political cadre in case he reported you to the higher nasties, then you had to go to a group meeting to solemnly discuss communism theory, there you were to publicly criticise your comrades' political behaviour and be criticised back in turn so as to be a better communist chap all round! What kind of an organization at war is that? One would justifiably explode: what in hell an army like that at war was doing – to put it very mildly?

That was how a Viet Minh unit - platoon, regiment, division - operated during 1946-54.

Yet the war was still noble. True, it was largely directed by the Viet Minh who claimed full credit after the final victory at Dien Bien Phu, after many Viets had died. But there were others who fought hard against the French on the battlefields but refused to acknowledge Ho Chi Minh's leadership. These fighters were lonely, their cause the most just yet their mental and physical beings the most threatened – by the French and by the Viet Minh. Their number dwindled quickly from 1946-47 to 1954-55. Many abandoned the war to go back to towns under French occupation, lived a sad disappointed (in their view) life. There were also those who never went to the jungle but operated within the cities and, alas, were even put into prison by the French at one time or other. The esteemed writer Khai Hung was one example. Vo Phien, a fighter for many years under Viet Minh's flag went back disillusionedly to town. At times some of these were loosely called the Nationalists, but the party carrying the same name was always loose in membership, always struggled for supports, for funds, weapons.

These lonely and idealistic fighters lost out at the end. Khai Hung was murdered by drowning by the Viet Minh in 1947. Vo Phien was always hated by the Viet Minh, later by its successor the communist Viet Nam government post-1975, hated by them until his death in 2015. During his final years his son, who escaped to the US in 1975 as a kid with his parents, supported by them for a decent education, was now very much enthralled with the Viet Nam government and publicly denounced his father and the latter’s body of works (perhaps the greatest of literary Viet Nam) solely on ideological grounds. Good heavens, where is my copy of Sartre’s Nausea?

The idealists were a spent force too in South Viet Nam during 1954-75, never recovered – the US preferred to support corrupt governments such as the Diem’s, the Thieu’s, because these were established, moulded and given money for survival by itself.

I always feel deeply for the non-aligned fighters against the French. Were I 30, 40 years older I would have been tempted to become one of them. A month after arriving in Sydney for an Australian government university scholarship in 1973, sitting one evening at the desk looking out the ocean from a quiet house prior to university in ten weeks, I started writing a short story about them, a story about that past of the country. The ballpoint pen was finally put to rest at well past midnight among beer bottle, glass, coffee cup, pack of cigarettes.

It was written as a fighter’s reminiscence after the nine-year war. Like almost everything literary I wrote at the time it was done practically in one sitting, hardly having an edit the next day. I passed it on the editor at the time of the Sydney Viet student’s journal. A good chap, he published it the next month. When Tet came it won the readers’ short-story prize for the year. Many people liked it. Because …

Because it was seen as rather dreamy, passionate, lyrical? Perhaps it was also too romantic, too dramatic? Well, that evening I felt rather lonesome and romantic at the same time. On the young side of eighteen years, left the home country only a month ago. Christmas spirit was pervasive in this large but pretty town. I wasn’t religious but felt touched seeing people happy and busy on the streets looking forward to their festive occasion. Like the Tet atmosphere in Viet Nam – Nha Trang, Hue, Sai Gon, and all other places. In my mind somehow the past was always younger, more innocent, despite human bloodsheds and sundry odious endeavours. How could I, thus, avoid being romantic writing about those nine years, 1946-54?

I wrote in accordance with the setting and the protagonist’s perspective. Before and later, often using realist prose. Amusing, in 1976, 1977, at times the more skillful and realist pieces were well-received but somehow less “loved” than the one written that Christmas.

Fifty-two years on, I “repost” here that story, with only minor editing to make sure the dates and places fit well with each other. It is of course in Vietnamese. Due reference was given to its origin (the Viet journal in Jan/Feb 1974, and that it was extracted from the short stories collection published by my then Valentine in September 1974, Nha-Trang, Viet Nam). Somehow I saw and still see her reflection in the story. Due reference too for the 1975 image painted by a dear friend. It too was dramatic yet exceptionally beautiful, fitting the story quite well – how Miện would look in 1946, in 1954. I insert it here without an express permission from the artist, simply because I lost contact with her for more than thirty years. We always got on well. Trust she is well, and I shall at least buy her a finest glass of champagne some place if we see each other again.

I often wonder, even if the story is complete in itself, I wonder what would be in the mind of the two or three protagonists during the war. What did they think of each other. What anguish, what love, what hope, what longing, what disappointment, what triumph, what tragedy …

Why? Because I miss them, because I love them.

I wonder, too, if I ever discover the letters exchanged between them, particularly from the lady protagonist, Miện, and her Ha Noi of those years, 1946-55. I wonder very much.

Long Vo-Phuoc, winter 2025

... after so many years

Cầu Gió is now on the new Page "Cầu Gió" (Windy Bridge); access by clicking on the page-name or on "More" in the list of the Pages above. See also "In Brief" for a description.

(The Post "Counting The Years for Sai Gon" ("1973-76 & Rho" page) was written in 2015. It’s now more than fifty years from the spot, the ferry station, on the river of time when I was last in the city. Re-reading it I cannot add to, nor take away from, anything in it. I like the post, yes; the sentiments are still the same, from 1973, 1975, 2015, as now, 2025. Still miss the faces sketched in it, blurred by time or otherwise …

But perhaps, this year, I might write it again in Vietnamese, the old language that I still love, the words of which I once lived in. Wouldn't be e

easy, but I would try, LVP, April 2025.)

Đếm tháng năm cho Sài Gòn

Long Vo-Phuoc (1973-76 & Rho)

Vậy mà đã năm mươi năm từ khi Sài Gòn đổi chủ, năm mươi mốt và một nửa khì rời thành-phố. Nhưng ai đếm làm gì năm tháng đã qua ...

Thôi thì già-dụ mình đếm cây đường Pasteur? Hai hàng cây me um-xùm lề đường, hai hàng nữa mịt-mù lá xanh giữa đuờng giỡn cợt xe-cộ một chiều xăng khói ngất đầu ngất ngọn. Bốn năm cây số hun-hút từ đầu Phú Nhuận đến đuôi trung-tâm thành-phố. Bao nhiêu thì-giờ đếm cây, dù rằng chú trai mười lăm lúc 1970 nhất-quyết đến mấy cũng phải mất dấu?

Và đừng quên Công Lý bạn đời Pasteur, hai thể-xác song-song giao-hợp nơi vô-cực. Ai bảo tụi Pháp không xây nổi đường-xá nửa phần tốt đẹp để bóc lột dân tình Việt Nam?

Hay là mình đếm đèn đường khi anh chàng mười tám hùng-dũng chở thiếu-nữ hai mươi trên cái “PC” của cô ta, Thu, từ Gia Định đến cái quán chịu choi hợp-thời (trên Đoàn Thị Điểm?), lăn ly cà-phê sữa ngón tay mắt chết đuối trong mắt cô nàng như thể không còn ngày mai để nhìn, phiêu trong nhạc phản-chiến như thể không còn âm-điệu nào sau đêm nay để nhốt vào hồn. Mai và Nghị bên cạnh, mật mày mịt-mờ trong rừng khói thuốc lá. Có phải cà-phê những hôm ầy thơm lừng chào đón đêm khuya, đày giấc ngủ ra ngoài mùa hè vô-tận?

Hay là chỉ đếm những con đường (bởi vì cuối cùng cũng vẫn những con đường, phải không?), dù rằng đường cổ-hũ lãng-mạn hay khổ-sở điêu-linh, dù rằng đường mịt-mờ xe cộ rẩm-rộ hay đường đẫm mùi hương hoa sừ vĩa hè, dù rằng đường tanh tiền viện-trợ tân-đế-quốc Mỹ hay ngộp thở xàc người tham-vọng cộng-sản mùa xuân Mậu Thân. Có phải Nguyễn Phi Khanh ngày qua, ngắn và hẹp, những căn nhà xinh-xắn mảnh vưòn nhỏ xíu ẩn mình sau từong cao, chạy từ Đinh Tiên Hoàng đến đầu Hai Bà Trưng rồi kéo lên Phú Nhuận? Có phải người thân một lần sống ở Võ Tánh? Xa hơn một chút, có phải trong hẽm nhỏ Hoàng và gia đình bận-bịu vui tươi? Từ Chi Lăng có phải Hoàng và mình cỡi Honda những buổi sáng thật sớm đền Nguyễn Du hay Gia Long chỉ để uống tách cà-phê ngạo-nghễ trên hè đường rất đổi phạm-pháp, giữ thăng-bằng trên Honda mà mắt trông chừng cảnh-sát?

... Và ly bia cụng với Hải đầu đường xó chợ nào Gò Vấp, bên cạnh mũ sắt và M16 dày cộm bụi bậm chiến-trường. Tụi mình nói chuyện gì: đời sống của bạn mấy tháng qua trên ngọn đồi Bình Định từ khi mình đi thăm sau Tú Tài Hai? Hải hỏi, tại sao đời phải luỵ với nghiệp? Khi nào chiến-tranh tàn để hắn viết đôi dòng trên giấy giữa khi làm vuờn (đẹp như mộng George mộng Lennie của Steinbeck)? Và, minh có thật đủ tiền không để in cuốn sách solo đầu tiên của hắn (lời hứa thốt ra quá nhanh năm trước)?

… Gò Vấp xa một vực cái phòng sinh-viên nhỏ của bốn chàng choai-choai ở Minh Mạng – không đầu đường và không xó chợ. Anh của Tuấn là một chàng chỗ này, và Tuấn, đến thăm từ Nha Trang, ngủ trên nền xi-măng. Cơm trưa đại-học-xá lõng như cháo với vài thứ lạc-lẽo gí chẳng nhớ, “có sinh-tố trộn thêm trợ-cấp chính-phù”. Thiệt à?

Hay là mình đếm hằng-hà sa số cuốn sách trên Lê Lợi những chiều mưa nặng giọt mái nhựa (nhựa hay tôn?) bao hàng bán sách xôn. Bìa Pháp bìa Anh tưng-bừng, ấn-hành đầu tiên có lẽ cũng có. Một Camus thời-trang chỗ này, một Steinbeck phổ-thông chỗ nọ. Một Proust rất hiếm giá cao. Giữa đó là Võ Phiến và Bình Nguyên Lộc, phát-hành đầu tiên độc-nhất tất cả, nằm thờ-ơ. Có phải cũng thấy một Nguyễn Tuân hiếm-hoi ngày trước? Nhưng ai có tiền mua sách chuyến đi xa này, đến một nơi sách báo cũng ê-hề … Thú-vị hơn là nhìn cho thoả mưa tràn-trề mái tôn mái nhựa, là lặng-lẽ chăm-chú kỷ-lưỡng những cô nàng mọt sách tìm kiếm Larousse thế này English for Today thế kia. Giữa những hàng sách xôn bên này và nhà Khai Trí bên kia đường là hàng trăm tấm nước đổ xưống từ bầu trời xám, đổ xuống một rừng xe cộ xấu-xí chạy tới chạy lui, phát-minh loài người nhân-danh tiện-nghi và kinh-tế.

Hay là chỉ đếm những ngày không còn? Tháng Bảy tháng Tám tháng Chín tháng Mưới, và một vài ngày đầu tháng Mười Một? Để những ngày đó thành cổ-thụ trong lòng hay chôn chúng vào bụi thời-gian, bởi vì lịch-sử là điều vô-nghĩa khi ngoảnh lại với tâm-tình? Có nên thăm dò năm tháng với đôi mắt lãnh-đạm – vì giọt mưa bảy-hai bảy-ba không thể ngọt trên lưỡi hơn giọt mưa 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, và tia nắng mùa hè 1973 không thể sáng hơn bao nhiêu hạ trắng sau này?

Hay chỉ đếm những ngày cuối cùng trên cái gác nhà sàn Khánh Hội? Chỉ một hai ngày trước khi đi, ăn baguette thế cơm nhìn nước sông lặng-lờ dơ-dáy dưới sàn. Tiền-bạc trở thành hắt-hiu, rất hắt-hiu, nên vị bánh mì trên lưỡi ngọt như tất cà croissants trong patisserie Ba-Lê những năm sau. Sơn thăm từ Nha Trang, Sơn với ví tiền xẹp lép nhưng chia những tờ giấy bạc cuối cùng cho cà-phê, thuốc lá và thức ăn thanh-đạm.

Sơn hỏi, vòng vòng Sài Gòn trước khi mày đi? Thì đi, từ Bến Vân Đồn mình vòng cái cầu trước hết, rồi mình vòng, khốn chưa, mình vòng Nguyễn Huệ tiếp theo bởi vì tiện trên đường. Hiềm là mình vòng Nguyễn Huệ lúc đầu, bởi vì mình vòng Nguyễn Huệ lần nữa truớc khi về cái gác. Thành thữ minh vòng Nguyễn Huệ hai lần một ngày, để hương hoa nồng-nàn vây kín kiosks giữa đường, tràn lan khứu-giác linh-giác trong khi hai chiều xe-cộ trở thành con sông hai giòng màu bạc màu vàng cuồn-cuộn trôi qua.

Bao nhiêu kỷ-niệm chật-chội trí não khi chân bước trên đường mà tâm-tư mù-mịt trên mây?

Ở phi-trường Sơn và Nghị nói, đù má, mày đi rồi không còn nhớ gì. Mình nói, đù mẹ nó, nhớ chứ sao không. Điều gì sống bền hơn trong đầu óc, mặt mày bạn-bè hay mùi hương Nguyễn Huệ? Điều gì sống lâu hơn, những sợi suy nghĩ lẻ-loi trộn vào nước cam-lồ tuổi trẻ trong chuyến đi không ngờ thành vĩnh-viễn, hay là sự thật thời-cuộc những năm cuối cùng nội-chiến khốn-nạn này, khi hàng triệu người Việt chết phía Nam bờ Bến Hải, chết tuổi non tuổi già, chết không cãi-cọ triết-lý chiến-lược hảo-huyền Hà-Nội Mạc-Tư-Khoa Bắc-Kinh Hoa-Thịnh-Đốn?

cho những người thân, đã năm mươi năm,

Long Vo-Phuoc, April 2025

Counting The Years For Sài Gòn

(1973-76 & Rho) Long Vo-Phuoc

It is now forty years since the fall of Sài Gòn, forty-one and a half since I left it. But who's counting ...

Shall we nevertheless count the trees, say, on Pasteur Street? There were trees on pavements both sides. There were trees too in the middle, two lines of which, between lanes for cars and lanes for bikes. All these trees stretched three four kilometers from one end near Phú Nhuận all the way to the centre. It would take time to count them and, even with the determined mind of a busy fifteen-year-old in 1970, one lost track.

And let’s not forget Pasteur's companion, Công Lý, two parallel lines that met at infinity. Who said the French couldn’t build half-decent boulevards half a world away for their own exploitative use?

Shall we, say, count the lampposts when an energetic eighteen-year-old rode a “PC” - a moped - that belonged to a twenty-year-old, Thu, carrying her from Gia Định to a trendy café in the heart of the city (was it on Đoàn Thị Điểm?), over café noir looked at her as if there was no tomorrow left to look, listened to anti-war music as if there was no sound remaining to gather? Mai and Nghị were there, almost drowned in surrounding tobacco smokes. Was the coffee those nights fine and flavoursome, the scourge of many a sleepless night in a long long summer?

Or shall we simply count the streets (it’d always be the streets, wouldn’t it), whether old-fashioned romantic or teemed with truculent hardship of life, whether fogged with dust and petrol fumes or soaked with frangipani scent from gardens along footpaths, whether packed with downtown stench of corrupt money coagulated with american neo-imperialism or loaded with the rotting smell from dead bodies caused by communist ambition in a 1968 spring. Was it Nguyễn Phi Khanh of a time long past, short and narrow, full of well-kept houses and tiny gardens behind high walls, leading from Đinh Tiên Hoàng to the beginning of busy Hai Bà Trưng and onto Phú Nhuận? Did lost relatives really reside off Võ Tánh? And a little further on, was it off Chi Lăng that Hoàng and family once lived? From Chi Lăng did Hoàng ride with one those early mornings to Nguyễn Du or Gia Long simply for the pleasure of drinking café served illegally on footpath by the vendor, balancing on the Honda whilst one eye watching out for the police?

.... And nooks and crannies in Gò Vấp where a beer or two was shared with Hải, next to helmet and M16 freshly covered with frontier grimes. What did we chat about: how life has fared in the intervening months since we last saw each other on a hill in Bình Định? Must life have a pre-ordained destiny? When will war be over so Hải could write a few lines in between time organising his dream farm and garden? And, does one truly have any cash at all to help publish Hải’s works (a rash promise made the year before)?

... Gò Vấp was quite a world away from a room of four sharing mates in the university residence college on Minh Mạng (neither a nook nor a cranny). Tuấn's brother was one such roommate, and Tuấn, visiting, slept on the floor. Lunch was soggy rice and whatever else that skipped the mind, the rice mixed with "vitamins" generously supplied by the uni administration. Really?

Or shall we count the books on Lê Lợi those afternoons when hard showers fell on the second-hand stalls’ plastic (or was it tin?) covers? Titles many in French and English were there and, who knows, first edition copies perhaps aplenty. A trendy Camus here, a popular Steinbeck there, not to mention Sagan and such. A rare one from Proust with price to match. In between, Võ Phiến’s and Bình Nguyên Lộc’s were unfairly neglected, first editions all – did one even see a treasure by Nguyễn Tuân, he of a previous life's vintage? But who'd have money to buy books for this long journey where there would be books awaiting anyway? Wasn’t it finer to watch the rain spill over hard and soft covers, messing hair of the few serious-looking young ladies amongst chaps scouting for Larousse and English so and so. Between these stalls on the one side and the Khai Trí on the other, sheets of water covered countless ugly little cars, little motor bikes, six eight lanes full of tiresome inventions by humanity in the name of economics and practicality ...

Shall we, then, count the days that would no longer be? July August September October and a few days in November. 1973. Should those days live on inasmuch as those thereafter, or should they be buried because history is a lousy thing when viewed with emotion. Should one look back only with a detached soul – a raindrop in 1972 needed not taste sweeter than that in 1974, in 1975, in 1976, in 1977, in 1978, in 1979; and a sunray in summer 1973 surely not brighter than in any summer since.

Or shall we count, instead, the last days only, those days of having plain baguettes for dinner in a little Khánh Hội tin roof room above tepid water. Money was tight, real tight, so the bread tasted as rich and supple as anything from a Paris patisserie in later years. Sơn came down from Nha Trang - Sơn with an almost empty wallet but shared the last notes on café, beer, cigarettes and the most basic of food.

Sơn said, how about doing a few walks in this noisy city before you go. Well, let’s do it. From Bến Vân Đồn we’ll do the bridge first and, damn it, since it’s there, on the way, we might as well do Nguyễn Huệ next. It’s always hard to do Nguyễn Huệ at the beginning because we would do Nguyễn Huệ again on the way back to the little “attic”. So we do Nguyễn Huệ twice then, with flowers overflowing the kiosks, perfume overflowing the senses and traffic lanes mutating suddenly into silver rivulets.

How much memory could we store when feet on the ground and mind in the air?

At airport Sơn and Nghị said, fuck, you go and won’t remember one iota. One said, fuck, I would. Which is more persistent in memory, faces of friends or the fragrance of Nguyễn Huệ? Which is more persistent, snippets of thoughts that were overwhelmed by the elixir of youth prior to an as-it-turned-out forever journey; or the reality of the time, the final year or two of a vicious war where millions died, a million scarred and disabled, most of whom young, most of whom civilians and most of whom from South of the Bến Hải?

Long Vo-Phuoc, April 2015

"The Ogress's Reply" - North-East

A little stoned tonight (never mind the market) – but only from a glass of Margaret River’s Cullen cabernet sauvignon, 1994. Not a terrible drop. Certainly not from a joint of weeds like in the old university days (far and few in between the zillion puffs of tobacco).

Yes, I felt fine. Carried out a small part of an idea started yesterday. That is, putting in the Viet script some of the favourite chapters of "North-East". A mate told me recently he liked “Đếm tháng năm cho Sài Gòn”. Very nice of him. We arranged to have a bite to eat at lunch today in the Viet part of town, a place I haven’t been to for many years. The talk was gentle and flowing (though no vino or beer available) even if its substance was hard at times. He was the editor, just before me, of a Viet newspaper back in the early 1970s.

Old mates catching up after a long while, second time the last 50 years.

The piece from North-East is “The Ogress’s Reply". Any time re-reading it I like it a little more (almost like, forgive my immodesty, reading “Something I’ve Been Meaning To Tell You” of Alice Munro. I tell you, that is one of the two finest short stories of the world, ever (short, long, who worries?, they are simply sumptuous literary marvels)).

Thus I put the chapter in the language that I really love. Well a small part of it any way, but the part that I quite like - even though the novel is much more than the love between the two protagonists. Midnight comes, stoned/"phiêu", perhaps some other time for me to finish the rather difficult task. Difficult because it is necessary that, whether in Viet or English script, I must be able to breathe the same air (the same flagrance despite the bloodsheds and ruins in Europe and Viet Nam from the war years prior?) as Nicole and Nga did in their Paris and Hà Nội of 1955. And because I love them with more than a passing literary passion, need to be with them, my ladies who are forever beautiful, exceptionally broad-minded and accomplished.

(And the other fine, finest, short story? Well it was penned also by Ms. Alice. No surprise there.)

Anyway, enough mucking around, let's read Nicole's reply to Nga …

(LVP, May 2025)

Bà Chằn trả lời

(Saint-Germain, Mai 1955)

Vậy thì, Nga yêu thương của mình, vậy thì em muốn biết mình là ai?

Em hỏi mình như thế tối hôm qua, nhớ không? Thì đây là lời tự-thú: mình là bà chằn, một bà chằn vừa đói vừa hung-ác, một bà chằn chỉ muốn ăn miếng ngon độc-nhất, và miếng ngon ấy là Nga. Bà chằn muốn ăn Nga cho thoả phút giây nào cũng được, Nga mà cải-cọ thế nào bà chằn cũng cứ ăn, cứ ăn ngay. Ngoạm ngoạm ngoạm thân-thể em, Nga yêu thuơng, bà chằn chỉ muốn ngoạm ngoạm em cho bỏ ghét!

Mỗi lần hai đứa mình dạo phố, mỗi lần như vậy mình không hiểu nguời ta có biết đến bí-mật khủng-khiếp giữa chúng mình, giữa hai cô nàng tân-thời tươi tốt đẹp-đẽ (không thể chối đuợc điều này), không hiểu họ có biết rằng mình, Nicole, chỉ muốn về nhà gấp gấp để ăn thịt Nga. Mình trông dáng bộ đàng hoàng, nói bon jour này nọ nguời này nguời kia, còn Nga thùy mị nhưng sao sắc-sảo và vô cùng sang-trọng với nửa nụ cuời (sung sướng bao nhiêu thấy nụ cuời của em, Nga, Paris hay không), nhưng số-phận em đã an-bài khi đêm đến, món cơm tối của mình sẽ dọn sẵn, món đó là Nga và em không thể nào trốn thoát. Đâu là móng nhọn của mình, à nó không trồi ra lúc này, nhưng đêm nay sẽ nhọn hoắc để mình vồ Nga trong hai bàn tay, để mình đem khuôn mặt diễm-ảo của em đến tận mật mình, vầ số- phận của em đã an-bài như đã bảo, đã an bài Nga vô-vàn thương yêu.

Long-ago prose (1973-76 & Rho)

I happened to come across a few old things this morning. Amusing (this really is a wrong word), is it because it is now half a century from the eventful days of 1975?

Found a prose-poem I wrote back in October 1973. I remember it was rainy those days, staying in a mate’s house in Sai Gon waiting for the ticket and visa to board a plane.

tháng 10/1973

Võ-Phước Long

Fallacy and Idiocy (A Contemporary Landscape)

These last few weeks have been quite busy in the financial market place. I also have non-monetary tasks to do.

The Assault on Ukraine’s Dignity (A Contemporary Landscape)

First, the threats, the snubs, the insults, from the leader and sundry acolytes. Next, the nasty siding with a blatant aggressor at the UN against a long-suffering victim nation. Then, the well-advertised malignant desire to grab that nation’s assets. And finally, finally, the unjust unprecedented assault.

Making a Map (Maps)

The news came in December 1974. I was a student labourer, broke, worked during vacation for some decent cash in Mount Isa Mines (yes, “MIM”, now defunct, taken over well and dusted). Rho wrote from Sydney; she said, I didn’t realise you were famous. She was concerned, loving, affectionate.

Waiting for Aphrodite (Time Slows)

When very young I didn’t know her, certainly not sure where she graced her existence. No one told me things. The first time I heard of her was in 1963 or 64, caused by a book by the pre-WWII author Khai Hung, a celebrated Viet novelist who believed in liberal values and wrote clear proses. The two concepts were alien to the country at the time. From that book, in my mind she started to manifest in colour, in texture. I was slowly falling for her. It’s a meandering way of falling in love but you would understand this simple axiom of human emotion: the longer and slower one falls the deeper one ends up in the abyss. I happen to know also of the immediate and passionate kind, and this too can last a long time, can be forever. But slowly falling is what I writing about here, these lines, these paragraphs.

.....

My Lady, these crude passages are homage to you. They may not be worthy to be graced upon by your celadon eyes, I understand. I’m now older, the stanzas have lost their power. But my love for you, my first Aphrodite, is still with me – real, burning from here to infinity.

Long Vo-Phuoc, mid-late northern autumn, 2024

In Memoriam, Alice Munro, 1931-2024

Thank you for every one of your more than hundred stories - every one of which, during the forty years that this simple soul had known of you, remains without fail luminous yet penetrating, as hard as ever, and always, always, a pleasure to read again and again. More than a pleasure, really a way of life.

Tết

It is overcast today, the first day of Tết. In fact it’s sprinkling – is that phùn, the raindrops that floated in the air in Ha Noi from what I read since sixty years ago. See, the rain in the lunar January of Hue was always heavy, same with Sai Gon. Nha Trang? Dry and sunny – as it usually was.

According to memory, at any rate. For a little amusement I don a tie, giving a nod to fifty years not seeing a real Tet. The polar-bear tie is nowhere to be seen, but we are not whacking the Nasdaq on the head today, are we (are we not?)? So a sepia-striped Georgio Armani will suffice. Let's leave the whacking job on the USD 1.8T Nvidia, the 3T Microsoft and Apple, the pushing and shoving Facebook (good heavens, at 1.2T green dollars), et cetera, for the younger polar bears of this world. May they stay tough and their analytical skills and financial resources last for longer, despite what Keynes said, than the idiocy of boys clamouring for new tech fads in the face of sputtering economies of China and Europe, of populist or authoritarian governments’ tendency to impose laws against upstarts, of world simmering tensions between the big boys, of competition and the dilution of new technologies …

But oh look, it’s pouring now out there. Phùn, what phùn? What phùn, dear Khai Hung and Nguyen Tuan?

I will treat the passages above as a hello to a habit on days like this, long ago.

February 2024

The Silk of Hà Đông (1973-1976 & Rho)

May 1973, bãi Dương

He received her letter, her essay, of the poem in the afternoon, the mail coming late in the area. He hurriedly opened it, made a little mess with the envelope (never forgives himself for that in the years to come). He read the first line, “My dear …” , then the second: “I never got over these two lines of Nguyên Sa”.

.....

Sài-Gòn, 1957 ... Sydney, 2024

The celebrated Áo Lụa Hà Đông of Nguyên Sa was written in 1957 in Sài Gòn, three years after the country was divided into North and South. There was peace – if only for a few more years. It is the most loved and most famous Việt poem after 1955. It is about two lovers and the silk of Hà Đông that was the áo-dài the girl wore.

Hà Đông is a province a little south of Hà Nội, capital of the North. Before 1954 it was famous for producing the finest silk for the country. After mid-1955 there was no longer commerce between North and South, so any Hà Đông silk of an áo-dài that a woman wore in the South would be a thing from the past, a lovely memory thing to be treasured almost above all else. It’s sentimental for me to imagine of such an áo-dài, made by such silk, that was worn by a bride on her wedding day prior to 1955.

This is the setting of the poem: two lovers, the girl extraordinarily beautiful, the boy a poet, sitting in a park in the October of Sài Gòn’s 1957. The calendar said it was October but it’s still tropically hot and humid you understand. So the boy pulled out an autumn from his Paris memory, because he lived there a few years back, to the Sài Gòn park and fervently believed that it, the autumn, chased itself around them, around his beloved who wore an áo-dài made from the Hà Đông silk, made on an autumnal day in Ha Noi some years before. He believed in such things, and told her that he loved her. He did all that, you see, because there was, as I had said, peace in Sai Gon, in 1957. I feel for the pair of lovers, I feel for her Hà Đông silk, the poet's too of course, but above all, without saying out loud, I feel for that peace of the Sài Gòn of 1957.

I first read the poem long ago, and thought off and on about translating it into English since 1973. Not seriously for the nearly half a century. Not only because poetry translating is a gross act of betrayal, but also because the poem itself is fiendishly difficult to be brought into another language. I had translated another poem of Nguyên Sa, Paris, one of Linh Phuong, one of Trinh Cong Son, and one or two of my own the last decade or two since retiring officially from the market, and I like those attempts of mine in a moderate way. But The Silk of Hà Đông is particularly defiant. Not simply because it’s the finest of verses or because it’s beautiful in images and lovely-beyond-lovely wordings. Not simply as such. It is also exceptionally romantic, like no others. The line “Mà mùa thu dài lắm ở chung quanh” must have dropped on the poet’s lap from the heavens one day in the Sài Gòn of mid-1950s.

And it, too, reminds me always of my Nha-Trang of 1973, and Café Tín-Mỹ, and the lovely person sitting in front of me on so many occasions, a person a little younger than I was …

So, could I make it into English lines that might appeal somewhat to my half-dying romantic self - the self somewhere from a pocket of the mind?

Fifty years on, in 2023 in Karlsruhe, Germany, I had just completed a personal literary task. I then had a go at the poem on the last day of October. This was when autumn swirled outside my hotel room, swirled above my head when I walked the city and the large famous park, attacked me with its red its gold its yellow when I wandered through the university (the KIT, Southern Campus) in the dark, at night, the pathway yellow lights among a little drizzling rain, swirled when I sat in cafes and restaurants looking outside. It was mid-late autumn, you see. Writing Nguyen Sa into an English poem those days I was drunk from words and alcohol, struggled with the lines and the memories.

But I completed a draft or two. By the time I left Zurich a week later it became the fifth draft, and I was 20% happy with my translation. A 20% probability is pretty low – you couldn’t make a living with that going to the battlefields of the marketplace. But at least it’s not 10%.

In Sydney over the Christmas break just past I finished the twentieth draft, and now my personal level of satisfaction rises to 75%. Not bad. By the time I truly stop editing this digital page it would probably become the fiftieth time. Well, what can one do with certain matters in life …

By the way I found seven English versions of the poem from the net, spanning the last seventy years. From the web-site https://viethocjournal.com/. Some of the attempts were from a Việt author or two but somehow I'm not sure if any of them was a poet. Anyway I put them in the images below. Reading this article on a computer would help the reader see it in an orderly perspective – never mind a little phone with its restricted frame, restricted space …

By the way, also, the poem was adapted into a well-known song by Ngô Thuỵ Miên although sadly the composer missed three stanzas in it – could have composed more notes to suit the extra lyrics. Duy Trác felt the sentiments well when singing it before and after 1975, Khánh Ly was soulful in 1976 in Sài Gòn, and Ngọc Lan did a nice gentle interpretation later in America.

For M and 1973, with love

Long Vo-Phuoc, 2023-24

Seeing in The Mind ... (Notes on Viet Lit)

In the late 1960s I read many of Võ Phiến's short stories, memoirs, novels, including Giã Từ (Farewell) published in Sai Gon in 1962. Reading Farewell I was quite amazed by the author’s unusual turn of phrases as the story unfolded, many parts rip-roaringly funny, many parts heartbreaking. His was a unique and refreshing style of narrative for the period, 1950s, 1960s, leaning strongly on realism – the prose clear and immensely rich with details. There was a strong underlying irony throughout the book - irony, sarcasm, but always under control, never malicious, never ugly, never lacking humour, never lacking depth or perception. I liked the book very much but thought, at the time, it wasn’t as attractive to me as a later work, Một Mình (Self). I was 14, 15, able to perceive the townscape of Hue, Nha Trang, Sai Gon of the mid 1960s but not yet imaginative enough to truly feel for a Qui Nhơn of 1945, 1950, 1953, 1955 …. At the time I didn’t fully fathom the intricacy of my country’s history during 1945-55. A few years later, and continuing for many afterwards, I delved further into that eventful period of the nation. In literature one feels, then one learns. The feel always overwhelms the learn. In history, the learn would first take centre stage.

Time passed, somehow I didn’t revisit Farewell in Viet Nam. But it so happened I came across the book not so long ago, here in Sydney, after well more than half a century. I closed my eyes and saw in the mind the setting of Viet Nam in the 1940s, 50s, the province Bình Định in particular. The propaganda fifty years ago, from the South, the North, from France, from the US, China, the Soviet Union … from self-serving Christian priests and Buddhist monks, gangster politicians, gangster bureaucrats, on and on to the nasty street gangsters, well, had now all scattered away in the wind, insignificant, odious.

Long Vo-Phuoc, 2023.

Cố - Quận (1973-76 & Rho)

Bởi vì cô bạn đã hỏi

Nên những giòng đơn-giản này

… viết ra.

The 1838 Map of Viet Nam

In 1838 the Oriental Lithograph Press in Calcutta, India, printed about 100 or so copies of the map of the Kingdom of Viet Nam. The map was comprised by the Jesuit scholar and missionary Jean Louis Taberd (a French Lycée in Sai Gon would bear his name after the French ate up the country in 1884) in, surprisingly, the brand-new Viet writing language using Latin alphabets. Don't forget that in 1838 Viet Nam was sovereign with King Minh Mang at the apex and Chinese Mandarin the official writing language.

The rare map is the earliest and most detailed one of the country: there was a 1764 map of the South-East Asia region, in French - nothing compared to this. There are a lot more details in it of the Southern (“Đàng Trong”, under the control of the Nguyễn Lords) than the Northern, simply because the Nguyễns were more open to foreigners, to commerce. Note also that towns such as “Sai-Gon” or “Nha-Trang” weren’t known to Taberd at the time, if existed formally as such at all.

Most of the original prints were lost through neglect and war. I’m sure what remain now are mostly in libraries, some in Viet Nam, some in France, some in Russia and China, maybe one or two in London or the US, and maybe, but unlikely, one exists in Australia. Probably not more than a dozen all up in the world. One or two perhaps in private hands, those eccentric private hands. One came up for sale a few years ago in Canada via Abbey Books, in "very good condition".

Map-making is a supreme art of humankind. It is a combination of art and science, of poetry and adventure accomplished via a sea of calculations, drawings, errors and trials, of the losses of lives, and of the pollution from the nasty smell of colonialism’s gun smoke (must every difficult achievement in life be a result of good and evil together?). See an example made in 1875 of India, Tibet and Sinkiang (my Page “Maps”, link above). Even those recent ones made in the 1960s by the US Army of Hue, Nha-Trang and Sai Gon are quite evocative, to me at any rate. In early 1974 I happened to draw a map, exhibited in my residential college and discussed it with a wonderful person who I had just met only a few minutes earlier. She told me maps might as well be memory in its furthest reach. For the countless times when we were with each other the next eighteen months, any time she said anything to me I saw immediately in her voice in her eyes on her lovely face the deep poetic wisdom of maps and of her mind.

Back to this, some of the best modern map-makers were Dutch. I wonder if any of my readers has a copy of Atlas Maior of Joan Blaeu of the Netherlands, published in 1665. That was the greatest achievement of maps at the time, and probably for a hundred years afterward. The immense atlas was republished by Taschen of Germany in 2005 under the direction of von Peter van de Krogt. It has been out of print many years now but I was fortunate to have bought one, pristine, from Amazon US for a hundred US dollars at the time. The huge book, hard cover, is still pristine in my hand after all the years of perusing!

At any rate I include the beautiful Taberd map here for the reader's enjoyment, to mark my fifty years away from the old country. The digital file in my hand is 9.3M jpg, lots of details. This attachment is just less than 1M. My Valentine printed it out for me in A2 size, and it looks good on the wall. It was downloaded from the "MapPorn" page of Reddit.

Long Vo-Phuoc, November 2023

Chapter 3 Nga (North-East)

When she was in mid-teens her mother used to say Nga lived in the clouds. Perhaps that was right. Her mind then never seemed to connect with her feet. She walked, and saw the treetops of Hàng Bạc. She sat, and inhaled the humidity of rain on the Opera. She closed her eyes, and in the mind touched the tip of Mount Việt Trì with her fingers.

A dreamer, night and day.

Hà Nội in the days of the mid-1930s was a place exuded with energy, even if that energy had no outlet to anything really worthwhile. People were romantic, full of new ideas learnt from the Western world (the French world, if one wants to be precise). People enjoyed a little more freedom from their “protectors”, five years on from the dark days of the Nationalists’ ill-fated uprisings. The white men’s economy in far-off lands, it was said, had come off the bottom. The colony here, it was said with further details, was becoming more productive. And privately the masters of the land pretended to see more docility from the subjects. After all one could put only so many in prison, could execute so many by hired machete hands.

Thus Hà Nội had many newspapers and tabloids, a few with literary and cultural pretensions. New books were published, fictions and poetry about love, playboys, modern girls, rebellion against the family tradition, memoirs of trips to Marseilles and Paris. Serious science materials were printed, the mathematics, the geography, and yes, the human biology with concentration on subjects such as sex and so on. It’s a new world.

And sometimes, it was true, there appeared passages on an entirely new brand of philosophy awkwardly labeled socialism, Marxism, communism. Yes, poverty was discussed in heart-breaking details and remedies argued earnestly, on occasions belligerently. Yes, France and her riches and exploitative ways were not necessarily the only wondrous model for humanity in the universe.

Hà Nội in the thirties, gay, free to enjoy harmless things, be they love, opium or gambling. Full of idealistic young men and women, all eager to learn new ideas. Most were French-educated in their twenties, some a little younger, and just a few very young like Nga.

Nga loved authors like Khái Hưng and Nhất Linh. Nga was much taken with poets like Xuân Diệu and Huy Cận. Later on Nga loved Nguyễn Tuân, especially, for his magical ways of conjuring colours and sentiments from the time just past, for his hard sharp strokes on poverty and the oppressed of the present (whenever turning a page of his books, Nga paused and wondered, another page, paused and wondered ...).

Nga was high-spirited. Nga was clever, pretty, liberal, well-read. Nga was everything Nga could wish to be.

Whenever got home her feet started to dance on their own accords. She could not wait to toss aside her school sandals and turn a few times in the little foyer doubled as living room and study for the whole family. She wanted to shout to her sisters, if they’re home already, on what had happened to her today even if it was nothing really. She wanted to ask if Thái learnt anything new from her high-browed history lectures, if she still talked to that toad of a wannabe lawyer cum activist, or if Thi struggled at all with physics in her baccalaureate. What about her Cậu, wasn’t he also home from the office, and if not, why not? What about Mẹ, why did it take her so long to walk home from the school? Couldn’t she hurry on because Nga was now waiting for her at home, wanting to tell her that human existence was truly meaningless, because at the end dust would become dust, because poets East and West had all said so – using the same precise words or not, what did it matter? We all will become dust and thus life is truly meaningless, isn’t it?

The meaning of life aside, one minor inconvenience in her life at the time was that Nga could not bring herself to rebel against her parents (or her sisters for that matter). It would have been perfect if Nga could identify herself with a tragic character in a modern popular fiction, Đoạn Tuyệt for example. Like Loan in it, Nga, or more likely her eldest sister Thái, would soon be forced to marry a traditional toad and would terribly miss an imaginary lover running around the country carrying on illegal but noble activities – like, starting a revolution against the French.

But no, Nga (or Thái, or Thi) could never even try to force her parents to arrange marriage for them and such like. The fact of the matter was that, instead of frowning on the three daughters for being day-dreamers and romantic high-browed nonsense, instead of that, they themselves engaged in something far more idealistic, far more nonsensical, far more deadly.

They were socialists, Marxists, on paper.

And before long, that sort of new-age romanticism trickled down to their daughters.

Was that how it began, she asks herself that every day. That my parents were two hopeless romantics, not happy enough in their love for each other, not happy enough in their bourgeois existence as minor public servants to the French, one a document translator and the other a high school teacher, not enough with a quiet life (would it be possible to be otherwise, regardless?) in lenient wonder at their daughters’ growth into womanhood. Not happy enough. They had gone further. They insisted on being revolutionaries in the mind. Marx and Engel and Lenin and all those more-than-foreign foreigners.

Thus Thái got to know this young toad marking time at the law school in her university. Liking him. Bringing him home. And shared his radical ideas around the home. He was downright dangerous in speech, in his conflicting Leninist and nationalist ideas – himself far from being au fait with the philosophy itself. He was confusing but always gamely bluffed his way out of tricky corners in arguments. He was confident, passionate. He was animated when talking to Thái and Mẹ about battles, the Great War, Napoleonic War ... the other two barely able to put a word in. Cậu, Thi and Nga looked on with frank amazement. He was full of emotions against anything that was not Việt Nam, his own definition of Việt Nam. He was an early member, a senior one, of a secret communist party. He hated the French yet loved to brandish his necktie, his ridiculous white suit bought when first came to Hà Nội a few years back. He was vain and not particularly brilliant. His stature was average, no taller than Thái, shorter than Thi and Nga who was fifteen. But he was infinitely ambitious, infinitely passionate ...

He declared, rather pompously, his love for Thái to her family. And Nga, loving each of her sisters far more than he would ever love Thái (different kinds of love, sure, but weren’t care and sacrifice the same denominators?), somehow had doubt even in her tender age. She very much wanted to know if he loved Thái, her own affectionate Thái, more than he loved his Việt Nam? But she held her peace, because what could one do about matters of causes and effects, matters of fate, non-existent or otherwise, and because Thái had deeply fallen for him. Thái thought of him as more worthy than anyone in Hà Nội, in the country, on the planet. Thái was besotted with him, willing to marry him in the middle of her university year, and Nga was shocked by the intensity of her sister’s emotion.

On Hàng Bạc, this last day of October, Nga looks up at the grey sky, dry eyes. Soon the misty rain will bring tiny droplets to her hair, forehead. She closes her eyes and breathes in her despair intermingled with the cool humidity. Did I have many days of this phùn weather when I was fifteen? Did I see grey, or did my mind seduce nature and bring blue always to the top of the money trees, the maples, the rare poplars the French planted when they had a break from imprisoning and murdering my people?

Dear loving Mẹ, I haven’t day-dreamed for many years.

She holds the two lapels of her threadbare jacket together, steering the bicycle with one hand. Must keep warm, and must hurry on to the meeting, or I will soon shake. In so doing make sure the eyes stay dry.

An apology to Khái Hưng, 1896-1947 (Notes on Viet Literature)

In 1975 I wrote a series of articles on Vietnamese literature and published them on the bi-monthly of Viet students in Sydney. I was the editor and manager of the journal, ran it as if in a delirium. The time was just after the change of regime in South Việt Nam, the forces from the communist North had won the war.

I missed the country that I had left nearly two years before, I missed the books I read there and would never see them again (communist cadres would burn them all within a year or two, as they had always threatened) – books belonging to writers I thought well of, many in first and only edition. The need to write something almost chocked me day in day out in April, May, in June, July … When you’re not even twenty, and the line in the sand had been drawn, clear, deep.

.......

(June 1975, Sydney)

Sơ-Lược Về

VĂN-CHƯƠNG MÌNH BỐN MƯƠI LĂM NĂM NAY

-

Văn-chương tiền chiến: dạy-dỗ hay không dạy-dỗ

-

Văn-chương miền Nam: tìm kiếm đường về

Mấy tháng trước, tình cờ tôi đọc lại một truyện ngắn của Vo-Phiến. Một truyện ngắn cũ. Tác giả viết về những dao động tâm hồn người Việt sau hiệp định Genève. Cái dao động ấy như thế nào, tôi đã cảm dược nhiều năm trước. Mới vừa đây, nằm trong căn phòng xứ lạ, tôi vẫn còn cảm được. Ai ngờ đâu, bao nhiêu năm xa Việt-Nam, tôi vẫn hình dung được sự đa diện văn chương nước mình.

......

Long Vo-Phuoc, late spring 2023 (and deep autumn in Hà Nội).

February no longer

Early the Sunday morning just past I crossed the part-intersection at Grattan Street. Part-intersection, because one half was well boarded up, under construction for a tunnel. It was a little after eight. Elizabeth became Royal Parade.

A modern monstrosity was behind on the left, a big car park hidden inside dark glass and steel cage, really not a such bad sight compared to many of its cousins built in large cities. It was certainly brand-new. I started to brave myself for similar changes ahead. What did the line of an old poem say – blue sea turns into rice fields? And immediately, rather distressfully, I saw two large tree stumps cut down to the ground near the centre of the boulevard. Between a lane for traffic and double-tracks for trams.

I didn’t expect to see anyone on my path, and there would be none for a while. I suddenly realised, despite ridiculous expectation prior, that I might not be able to meet that young chap on the way. There was no worthy probability for that to happen, only hope. A silly hope, that was true. But when you’re nearly seventy you ought to be allowed a few slivers of such a thing.

I looked at the boulevard more properly, further up in front. Two lines of large elms, with typically black trunks and branches, running along the footpath almost to the horizon. Across a wide traffic lane (but no traffic, you understand) next to me, one more line. Across the two tram tracks, yes, the same, another line. Across the traffic lane the other side onto the opposite footpath, well, one more. Twenty thirty metres apart for every pair, five lines of trees, on a stretch of more than two kilometres. Probably four hundred specimens all up, more than a hundred years old. Speaking about a lavish endeavour at the turn of the last century, when labour was cheap, time and materials plentiful.

I was much relieved. I thought there would be more than just the two forlorn stumps at the beginning. But really that’s all there were. Quite likely because the new tunnel had to go through the roots.

These trees were English elms, the fallen leaves in late autumn carrying a bright yellow hue. The leaf fit well inside the hand - I used to have a similar one in my old house of nearly thirty years. I crossed the empty traffic lane and stepped onto the wide nature strip near the boulevard centre, stepping on a yellow carpet. Soft and thick under my shoes. I walked a length before getting back to the footpath. The university ground was on my right – gate 13 beckoned for a quick rest on a stone bench between old buildings, such I knew well enough, even if there had been a passage of time in between. But no, I had to see him, my young friend, before time blurred his face and my eyes could no longer see the details. I walked on, occasionally looked up to the leaves on high, abundant still in mid-June. What could I say, I loved these trees, these leaves, this time of the year. I loved this walk – even though this being only the second time, that was true, but like an old lover who always remained graceful and beautiful, for her time and frequency were never paramount and neither really was even passion. Instead a slow process had started that ripened the memory of her, the opposite to the mills of “god”. It was the slow-burn haunting of love, not the delayed retribution for sins.

I lowered my eyes, looked ahead. There was now someone with a pet dog further on, and then, was that him, my young friend. My young friend, my old friend, walking with eyes looking up the tree tops?

If it was him, was he thinking of Công Lý or Pasteur when the world was still young, of the tamarinds covering the two streets. Four lines of trees each street, between pedestrians and lanes for cars and lanes for bikes. The trees were planted long ago by the French. Not as grandiose as Champs Elysees but exceptionally beautiful. Nearly three kilometres long, those streets, parallel each other. A thousand tamarinds all up. A hundred years old, give or take.

February 1975, when the young chap walked the Royal Parade, when the tamarinds of Pasteur and Công Lý still lived fresh in the mind, still compared well to the elms of the Royal. When the two Phú-Nhuận to Sài-Gòn Central routes laid alongside the Brunswick to Melbourne CBD, showing off their deep green shade.

February 1975, when Janis Ian pronounced that her slightly earlier world was younger still. But never mind that intricate detail of the delightful Ms. Ian for a moment, that moment in time of 1975 was young, very young, to the chap that I once knew. How many such Februaries existed in a lifetime of a sentient? Before welt- and realpolitik came with all its brutal force, canons and ideologies, with retribution and without love.

February 1975, was it a month that was now no longer in the calendar of the mind, when the tamarinds had ripened their fruits long ago, had dropped offsprings on the ground – rotting, eaten by sundry birds, sundry worms, crushed to oblivion by sundry shoes, sundry bare poverty feet, such as they were.

That friend of mine, the young chap with eyes so wide and mind so hopeful, not even twenty, did I really see him the Sunday morning just past? Coming to this boulevard after nearly fifty neglecting years simply to walk along these elms, did I really sight an old friend? Or was I, am I, now too jaded to even concede that my eyesight, my mindscape, are no longer equal to the task of dissecting memory?

One afternoon in a past landscape, February cradled the chap under the summer green of four hundred elms, the green of a thousand tamarinds. One step out of time, somehow, and February no longer, the tamarinds died. Only the late autumnal yellow of the elms remained.

Long Vo-Phuoc, winter 2023

(Note: Speaking of cheap and plentiful labour, above, when the Royal Parade elms were planted, I couldn’t resist a note here. At least in Melbourne, then, labour was paid for more or less in accordance with the law of the land. Anglo-Irish labour for the tree planting, mostly. Not well-underpaid, forced or slave labour all over the colonies of Europe at the time: much of Asia, Africa, Latin America, the US South, and in Australia itself with Chinese labour for the early gold rush. Who would ever forget the four to six million Congolese slave-labourers killed by Leopold II and his Belgian henchmen in the name of greed for ivory and especially rubber more than a century ago? Hitler and Stalin were nasty beyond nasty. What word, then, can be used to describe Leopold, him among the clubby European royalties (yes, the English especially with cousin Victoria) and friendly republics at the time?

Things are still difficult in many parts of the world today – where women, in particular, continue to suffer as they did decades and centuries ago.

The Elms image is a photo from my phone. The Tamarinds from Google Image.)

North-East - Chapter 9

Monologue

(Nga’s personal notes. Cao Bằng, autumn 1947.)

The war rages on. A nation's bewildering romance of autumn 1945 has faded. In its place is the numbing reality of lost and found, found and lost. My days struggle under the numerous tasks. The minutes between days, in the still of darkness when midnight comes, lengthen, intolerable.

I write these pages to escape those moments. To clear out the thoughts mutating in them, clear out the mind, clear out the festering. A waste of precious paper, that is true. A frivolous activity, perhaps - but surely there must be leniency from the altar of ideology.

…..

Hồ and Giáp barely escaped French claws in Bắc Kạn. The comrades were relieved but tension has since steadily built up. This novelty of our time, the paratrooper assault. Soon the enemies will attack our Cao Bằng redoubt. The town will likely be lost but the village is fifteen kilometres away. If needed we simply filter into the Chinese jungle leaving non-essential equipment behind. After a while they will withdraw, and we will be back. As always they need a decisive fight. As always we deny them one. That’s the way war works for the weak, weak in firepower but steely in the mind. Or so Hồ insists, casualties notwithstanding.

I work efficiently. We were even commended at times. But there is a hollow detachment in my soul. Not a death wish in face of the battle ahead, no, simply an indifference.

.....

Occasionally I miss a café noir. Put the pencil down, a break, and memory of the dark liquid on the tongue stirs. So many nuisances for a bourgeois habit. Isn’t it easier to forget it altogether? But it’s almost a year.

It’s almost a year since the last shared cup. Autumn then was deepening. The days darker at five and six. The Celsius fell steadily. The humidity pervasive. It rained a little, every day.

Like now.

The young comrade said the French had started to demolish the area to build new homes. February. Making homes for the returning French. The bulldozers carried fallen comrades’ rotting bodies away to the dumps.

Bones and skins – unpleasant creatures still feasting on.

The comrade looked older than his twentysomething. He said, “I’m sorry comrade chị Nga”. Why sorry. Because he himself had escaped with the barest margin of life over death?

I miss Thân. I wish I had loved him near as much as he loved me. I wish I was, am, less of a cynic.

Thân and the last café noir. How we miss the details, the profound and the minor. I know: because all are no longer with us.

......

Liễu said, it hurts seeing you bottle up anguish inside, can anyone do anything? She is loyal and affectionate, more so than ever. Cheerful, kind-hearted - there is a nice local admirer for her, still early days, but she never asks him here, our little home and work station.

I said, I am not really against socialising myself with the comrades, but I am used to deal with things this way. She said, you push even the closest of friends away when you have a bad problem.

The mask that we wear.

The ronéo printer is ancient. It was probably never good when new, a lifetime ago. We actually paid for it, second hand at a much reduced price, at the same time with the battered typewriter, a small supply of stencils, paper, ink, sundries. From a dilapidated printing house in Cao Bằng last winter. The stencils will soon run out, what remain are creased in places almost like a crumpled page – streaks of carbon black showing. The production is rudimentary, and both of us smudged from head to toe on printing days (often Lieu asks, there are black spots on your cheeks, your lips, eyelids, would you like me to clean them for you – even though she’s no better). A dozen pages in all for each edition, every page, almost every space, covered with words, small font and narrow spacing. Fifty copies - any more and the stencils would disintegrate. And the paper has to be saved up for later editions, for the classes, for other Party work. Every three months an edition, when the change of seasons comes. Each copy passes from hand to hand, by the hundreds, this side of river Lô, even further on to the Red and Brown basins. The comrades would read and compare with other newsletters from other Liễus other Ngas.

Everything is manual. I am an old hand at rolling stencils since well before the autumn-revolution days. The half-broken wooden handle must be manipulated with care. I can even feel the worn-out bearing balls, judge the amount of ink, press on the stencil here and there to make sure the ink is evenly spread out – “evenly” is a very generous term here. For each page I attach the row of holes at top of the stencil onto the gauges and spread it out; a delicate task with almost no margin for error. I wait a little, then roll fast for the first few copies, gingerly for the next few, fast again, slow again, always checking on the sheet coming out. Judgement, judgement. Liễu and Cả watch as if in a trance. They probably watch me more than watch the machine. My perspiration seeps from hair onto the forehead. I feel strands of it on my cheeks. My shirt sleeves are rolled up high, arms alternate between warm from the effort and cool from rest in between the pages. My neck becomes hot.

The last occasion Liễu said quietly, standing next to me, “you’re so beautiful Nga”, eyes shining. The noise generated from my arm on the little iron workhorse half drowned her voice; the little table shook as always. I was embarrassed, but the machine demanded full attention.

Every season. For almost a year now. On those printing days I discover I am still vain. So tiresome, vanity. But I am a young woman, not yet thirty.

They like our work. Snippets of very general news of the struggle, carefully considered and discussed prior at the committee. Helpful hints on health, hygiene, food and clothes - what little of the last two items that can be had. Present too are rehashed anecdotes on troop spirit from old Viet and recent Soviet travails - mushy stirring tales all but I am careful not to cheapen them with flowery and overt party-loyal language.

It is not easy. Many times I have to step away from the Nga that is still a stranger at heart to the Party. This is a task I have committed to do, thus I must do it well. Regardless of personal feelings, bourgeois reactionary tendency from long long past as a Party theoretician may fairly accuse. I want to contribute to the struggle. I want to offer practical help. Tighten the mind, I tell myself.

Liễu too contributes. She writes carefully, types diligently, striking hard on the keys to penetrate the recalcitrant wax of the stencils. We will die young from heart diseases, she rues. She is happy, innocent even. Her eyes at times are red, baggy, like mine. We hug each other after an edition is done. Her embrace is tight, giving, while mine reserved, reluctant.

Young Cả never refuses a task no matter how trivial how physically arduous. He brings timber for the heating of some of the numerous drums of water that he brings also. Yes, for our Hà Nội decadent daily wash – at night in late autumn and winter when it is cold, but we don't tell him that. He once offered to bring some chicken meat, some tasty fish maybe. We said no, thank you Cả, we are vegetarians, not buddhists but vegetarian atheists in Uncle Hồ's revolutionary spirit, and we three all smiled, Cả reddening slightly. He can read now, and is very thankful. It takes him only a few days to finish a newsletter. He distributes the copies to the various post comrades, by foot - a bicycle not yet available for him, never a complaint, always with a bright smile, bright eyes. Occasionally he practises with a rifle when temporarily in hand – more often these days coming from China. And a hundred little unpaid tasks demanded by the Party machinery, in between farming, helping with sick parents, taking care of small siblings. There are a thousand like him in this province. Many more in the North-East.

There is spirit in this struggle, yes, spirit intermingled with coercion. If I could only find a personal hope to bring into it ...

....

There are few books here, there being little room for such burdens. I remember a passage from a writer ’s memoir – was it Nhat Linh’s “Westward Bound”? The alter-ego, twenty-one twenty-two, a non-believer in ideology or religion. After many trying and convoluted manoeuvres somehow found himself at the 1931 Paris colonial expo.

The young man was there, wind in hair and mind. By chance met an old Hà Nội acquaintance. They had a meal together, a young man and a young woman, deliriously exiled from home for that little while. Life brightened suddenly under a sky belonging to others. The young man said he was here and there on the way – waiter on ships and all. The young woman said, yes, she too was here and there. But it mattered not, they assured each other, because they were now in Paris. Can life sparkle in any other way?

Do we struggle through life so as to build an expo for others to meet, to renew acquaintance, to renew love, vigour?

Or more often than not we struggle in order to, simply, finally, attend others’ expo? Strangers in a strange land? To smoke a cigarette, have a sip of cafe, of wine, pretend to look at the trees outside the window so as to look at the soul of the love interest opposite? Really, are those us, we Việts who have never been so inventive yet who are always keen to fight, among ourselves and against others, and thus find not much else to do?

My sister and brother comrades, by all means build or attend expos. And not to fight through life.

As for me, there is no purpose at all to be at an expo, Hà Nội Paris or Moscow. I wish only to pave over midnight thoughts with pencil and precious paper, ironing out invisible cancerous cells. One day the midnight minutes will lengthen into days, into months. These pages must then be burnt into ashes.

......

The comrades had finally killed the writer Khái Hưng in Nam Định. Or so they whispered at the committee. The cadres there, loyal members all, demonstrated pleasure to each other, slapping each other's back, praising the determined cleverness of the men responsible.

They got hold of him in the countryside. They put him in a large canvas pouch, added stones. And threw him into the middle of the river. The deeds that men do, either side of the dividing line.

The deed that was done to this writer. One who never received a favour from the French or the puppet royal bureaucracy. One whom the French disliked, imprisoned even, because he was a progressive. One whom the comrades disliked, because he worshipped the rights of the individual above all else. A liberal with a pen. One who fervently espoused liberalism. One who, from this side of the divide I shall deeply miss.

I too believe in liberalism, mind and soul.

I was a little upset. I didn’t say anything. Perhaps that will be quietly reported to the highest channel. I smiled to myself – by all means do so. Soon later, cycling back home, alone in front of the table, the tiny blackboard, the printer in the corner - comfort things all, I realised I was still upset.

Khái Hưng. Was it that long ago when I read “Hồn Bướm Mơ Tiên ” when it was first published. “Nửa Chừng Xuân” a year older. And “Trống Mái ”, that strange bourgeois novel - so bourgeoisie, so far removed from the sad reality of this land, yet it was part of Hà Nội life. Trống Mái, where sexual feelings in a young woman threatened to overcome class, education, social standing, prejudice. Only threatened, never remotely had a chance to eventuate – a bridge simply too far.

Trống Mái surprised me. The narrative was suitably reflective of a spoilt rich girl, attractive, well-educated, modern. Sophisticated in a materialistic way. A little callous to begin with but never ill-meaning to anyone. A superb Viet elite product in the French mould. Vulnerability she had, but well-defended by the confidence of breeding and education.

The young woman had empathy, feelings, and with those came understanding and appreciation of the less fortunate. Yet there would be no radical ending. A ponderous tale, perhaps pointless, quite, but a tale well illustrating the empty French education of the Viet serving class. Well-learned, this new class, to be sure, but existed solely to serve the masters of the land. As long as one did not step astray: because there would be harsh penalty. A half-hearted liberalism offered to suit the mother country’s exploitative ways, much less than half of what a Khái Hưng would hope for. And so on to this day in towns and cities occupied by the colonialists.

My family, sisters, had stepped outside the constraint. Paid the price (how do the French and cronies feel, executing young women on grounds of ideology: the Inquisition all over again for modernity?). And all that once was is now reduced to this self, this self who writes these reactionary words when autumn is falling outside.

Nguyễn Tuân, Khái Hưng ... writers almost of my generation, ten twenty years older. I feel affectionate to them. I could touch them with my mind. And now one side, my side, had cruelly murdered him because Khái Hưng was a non-believer, on his own side. As cruelly as the colonialists and collaborators killed millions of Viets from battlefields and prisons for 80 years.

The odious dividing line of humanity who does harm to each other in the name of ideology, religion, greed. And in so doing we think we are closer to a higher being, to a purer self.

Yes, these pages must turn into ash one day. I only wish, when that happens, no harm would come to Liễu who shares this work station with me, my comrade and loyal friend.